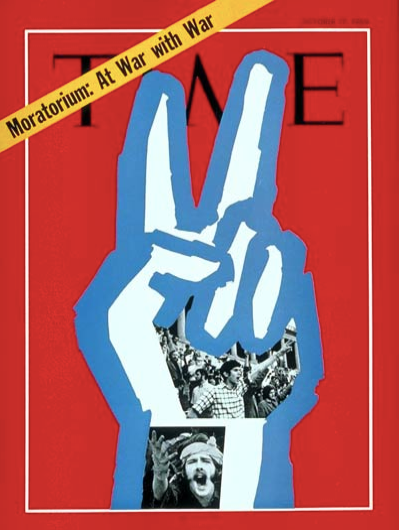

October 15, 1969: The Moratorium to End the War in Vietnam. A Pause for Reflection in a Polarized America.

/The anniversaries of seminal events that rocked our world fifty years ago are coming hot and heavy this fall. Today, we remember a time when we tried a reasoned strategy to attempt to deal with a generation-defining issue in a country as divided then as we are now.

By the time of the Moratorium, America had been involved in Vietnam, in one way or another, for nearly ten years. Any initial objectives for the war were long gone, the domino theory relegated back to the game it was named after, the war’s progress descended into body counts, the goal now so incrementally small that there was no big picture left or possible. Our defense secretary was telling us that if we killed more Vietnamese than they killed Americans, it was a good week. Period. The Killed in Action Numbers came out on Thursdays.

It was pretty universally agreed that the war was a disaster. What wasn’t agreed upon was what we were going to do about it. Half the country felt we should stay in Vietnam until we “won,” because America had never lost a war. The other half felt that we should cut our losses and get out—those losses being so obvious in the form of body bags containing young adults (many just teenagers) we were seeing each night for the first time on television, on the nightly news, just before dinner, when the numbers of killed and wounded on both sides were announced with a chart, like sports scores. No one could not know—or pretend not to know—what was going on.

On October 15, 1969, America was stuck in an existential dilemma. Who were we if we stayed in Vietnam? What were we if we left? Lines were drawn at the dinner table; people couldn’t talk to their own relatives; friendships were made or lost depending upon which side of the argument you were on. The country was at a loud and strident impasse—no one was budging. And the policies of our new president, Richard Nixon, despite campaign promises, were alarmingly close to those of his predecessor, Lyndon Johnson, who’d abdicated the presidency because he couldn’t figure it out.

One Day in October, Two Days in November, Three Days in December. . . A Strategy That Should Have Worked

THE NORTHERN STAR, NORTHERN ILLINOIS UNIVERSITY, OCTOBER 1969

A moratorium is defined as a delay, a postponement, to give time for reflection. The plan for the Moratorium that October was to apply this concept to ensure the country didn’t stumble blindly ahead in a direction that might be wrong. It was to be peaceful: to put the war on pause, while we reflected about how we had arrived at this point. How did the war begin? What were we trying to do? How could we bring it to an end? The theme was grief, sorrow, and solidarity, rather than anger and rage. It was important to demonstrate that a war protest didn’t have to be violent and destructive like the one at the Democratic Convention. Instead, the tent was wide and had room for anyone with doubts about the war and the direction of the country, knowing this cut across all segments of age, race, and economic status. The concept was to build a groundswell—to engage the widest representation of all groups and factions. You didn’t need to be a radical to be against the war. Your desire to end a war that had lost its way was the common thread.

And it worked—huge groups gathered in Washington (250,000), and cities across the country. The idea was to expand it month by month, to increase participation and demonstrate the widespread support across all subsets in the country—civil rights organizations, churches, business groups, universities, unions—to end this war that affected everyone. After all, who didn’t have a connection: a child, a boyfriend, a student, a brother, a cousin—some family, some connection, anywhere. A war experience enters the DNA of a country, our DNA. Our lack of power over its escalation gripped us all: it was time to build our side of the argument. What were Communist dominoes and saving the world for democracy, versus the loss of actual lives? Did we need new ways of looking at conflicts—of considering more carefully how we got into them, and the points at which we needed to get out? Just what were the ethics of unwinnable wars?

Students Went on Strike

The way this played out on college campuses—which represented the largest concentration of draft-age men—was in the form of “strikes.” Students were encouraged to skip classes and attend informal education sessions about the roots of the war, the options for protest, how they could regain power over their lives. Since Vietnam had been around through most of the students’ childhoods, they had grown up with it, and now were in it, without really understanding how the country had ended up where it was. It was time to revisit the Gulf of Tonkin, the French involvement, the anti-communist fear that ensnared John F. Kennedy. Or, to learn about them for the first time.

Ken Burns traces all this beautifully in his PBS series The Vietnam War, but back on October 15, 1969, no one was piecing it together, talking about what it all meant, what was really at stake, perhaps, versus what had previously been wagered in other wars. We needed new comparators.

Teachers were encouraged to suspend their syllabus of the day and discuss the war with students. The chemistry teachers balked, but the history and political science professors were in heaven. Students came, the straight (in the old definition of representing the norm) and the freaks. People were talking. Check out the excerpt from The Fourteenth of September that takes place on that date, and you’ll see that it was an opportunity for people to talk about what they felt, to finally ask their questions, to face their fears, to begin to understand rather than just react.

Time magazine said the Moratorium had brought “new respectability and popularity” to the antiwar movement.

The Aftermath

The Moratorium was a huge pearl in the string of events that eventually led to the demise of this long national ordeal, that would take until 1975—six more years—to conclude. Though the administration retaliated with Nixon publicly stating that “under no circumstances will I be affected,” he was. The event led to Vice President Spiro Agnew’s infamous speech when he called anyone against the war “effete corps of impudent snobs who characterize themselves as intellectuals” (which would have made an exquisite tweet in today’s world). Significantly, it also resulted in Nixon’s defining “silent majority” address, asking for the support of what he assumed was the vast heretofore quiet bulk of Americans for his Vietnam policy—that we had to stay and win. Peace with Honor, he called it. He conceded the point that South Vietnam wasn’t important, the real issue was that America would lose face. This was startling. From then on, the country knew what it was in for, what side he was on. And each of us had to decide what was more important—an escalating number of soldiers killed with no objective or end in sight, or maintenance of a perfect victory record? As a young person with your life or that of your friends on the line, you had to wonder if it was worth it when some old guy said it would hit us in our pride. We did not think this was a compelling case for the carnage, not a decade into this war, with a possible additional decade ahead.

Conversations were stirred up, assumptions were being challenged. It was a brief illuminating moment. We learned a lot. It was a start.

Power to the People

We all looked forward to the next phase of the Moratorium on November 15, 1969, which was to be the biggest March on Washington ever. We were empowered and activated to change the world. It felt so good, finally, to think that we could be heard. Illusions about this would be shattered as events progressed rapidly through the end of 1969/1970, but it’s instructive to remember that there are moments when progress did happen, and that it takes so painfully long. We paid a price for not listening to each other back then.

It makes you wonder if we need a Moratorium today—a time for reflection, to really think about the character of the country. Who are we if we continue on our current path? What are we if we choose another, hopefully better, one? We lose all when we stonewall and stop talking to each other. Perhaps our Moratorium is the impeachment process? It could be. Let’s be open. The sin of what happened fifty years ago was that we took so long to do what was inevitable in ending the war. The horrible price was in loss of life and damage to our national integrity. Our DNA is still frayed. There are echoes of what is at risk at present today in our country. There is a war going for our integrity. But there could be hope.

Like Judy in The Fourteenth of September who went through a Coming of Conscience journey to a decision where integrity trumped consequences, there are a lot of people today who are or who need to make a similar Coming of Conscience decision. Whether you agree with them or not, you have to admire their willingness to risk personal consequences for doing the right thing. We need so many more of them. The country awaits how this current Coming of Conscience moment will resolve—not just how it will be written about in the history books, but how will happen right now.

We can still change the world. . . if we listen.

All power to the people.

![momWWII%20photo[1].jpeg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/581992a5f7e0abdf04947525/1535419574442-WOB1100C6U3RM5DXOMY0/momWWII%2520photo%5B1%5D.jpeg)